I might be a little crazy to combine these two subjects, but they kind of go together. After you’ve chosen your pattern, you’re going to need to choose a yarn (in this scenario, you’re not a person who stashes yarn like crazy without a plan, so you get to go buy yarn; if you, like me, do stash like crazy, you can still use this information).

In our example from part 1, we were looking for a worsted weight sweater, so I’m going to continue to reference worsted weight. I chose worsted weight for the example because I think it’s the most friendly yarn to anyone learning a new technique—and sweater knitting is definitely a technique in and of itself. A worsted weight yarn beautifully straddles the line between being fast to knit while not being too big—and therefore adding visual weight to the knitter (note: many bulky weight and heavier yarns also make excellent sweaters, but they have to be wielded carefully in this knitter’s opinion).

The other thing to consider is your location. My friend who asked the question lives in Louisiana—not a place that gets cold frequently. In addition to general location, you should consider your general temperament. I tend to run hot, so I maybe don’t wear sweaters as often as some people might think (or as much as I might wish). If it’s not below 60°, I’m probably not wearing a sweater.

Fiber Content

If you live in a climate that tends to be warmer most of the year, or you run hot and don’t want to overheat, you can still consider wool yarns. I’d look at blend of wool with a synthetic or plant-based partner—something like Berroco Vintage, which I used to knit my Delancey, or the Berroco Elements I used for my Sislana.

I know cotton is considered the warm weather yarn but I respectfully disagree. In my experience, cotton is a really heavy fiber—and when you knit a whole sweater in it, it easily outweighs wool or a wool-blend. It may feel cooler, but you’ll get really warm just lugging that extra weight around. If you find a blend that is 50% cotton, that would be a good choice. My preferred warmer weather fiber is linen, which can be really incredible when mixed with wool or another, softer fiber.

If you’re sticking with wool, I strongly recommend a yarn with at least three plies. Single ply yarns are beautiful but they will pill so fast and I don’t think they’re as sturdy as a plied yarn. A sad fact of life is that wool pills, but in my experience, nothing plies faster than a single ply of yarn. Superwash yarns will also pill, a little slower than non-superwash. Some great options for sturdy and comfortable worsted weight wool yarns are Cascade 220 (Cascade 220 Superwash is also great, but it’s a different gauge than the non-superwash version; for me it works up more as a DK weight—just a general notice), Stone Hedge Shepherd’s Mill (I knit my Plum Rondo, shown above, using this yarn), Quince & Co Lark… we could be here all day.

On Substitution

There are a great number of reasons to substitute yarns in a sweater—price point, fiber sensitivities, availability—but if you can, I strongly recommend working in the yarn the pattern uses. I used to substitute yarns all the time, and I still will from time to time, but the things you really love about a design are in large part due to the yarn. My Sislana would have been swell if I’d used another yarn, but it wouldn’t have been as great. Likewise, the sweater I’m knitting now (Daqin) would have a different drape if I’d substituted another sport weight yarn. I’d say I’m about 50-50 on substituting yarn (I’m using a different yarn for my Stoney Brook when I get around to knitting it, but I compared the numbers and this should work out.

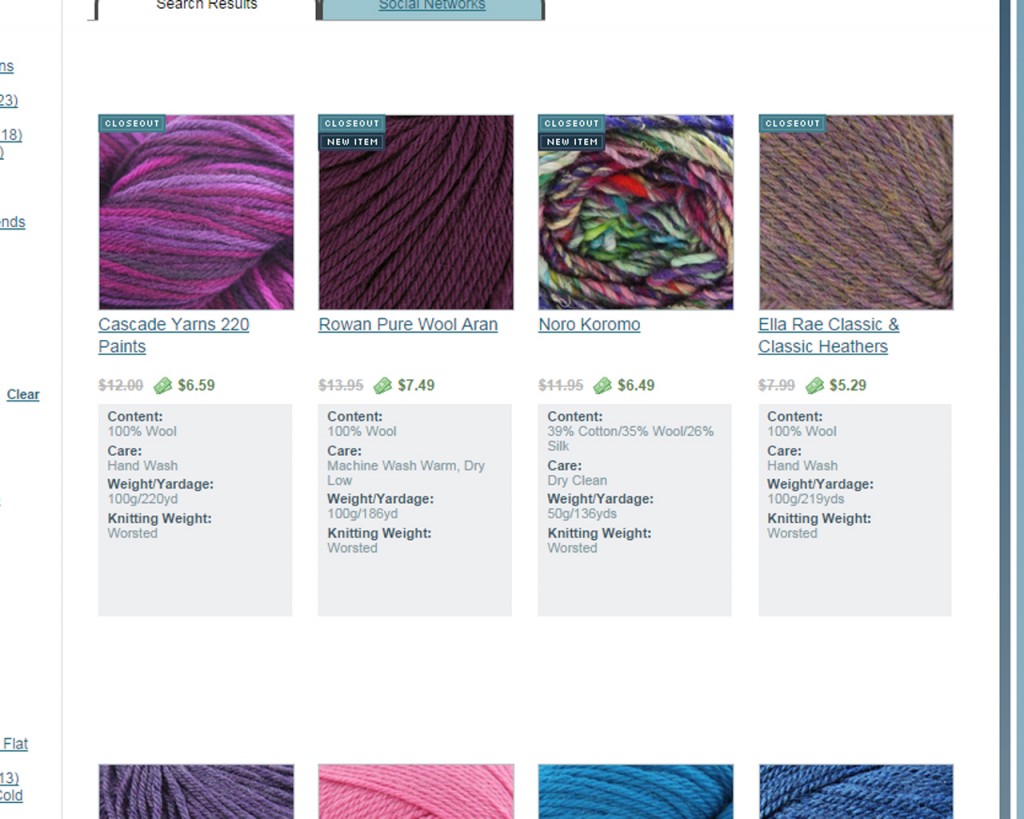

So if you are going to substitute yarn, do not just go by the labeled weight. There’s a lot of wiggle room in the weight categories—that’s why they list ranges in either the gauge (stitches per inch) or WPI (wraps per inch; in my opinion an antiquated and completely unhelpful method for determining yarn weight). I like to go to the weight category on WEBS and look at the yardage per gram of each skein.

All of these are “worsted weight” yarns. The Cascade 220 is 220 yards to 100 grams; Rowan Pure Wool Aran is 186 yards to 100 grams; Noro Koromo is 272 yards to 100 grams; and Ella Rae Classic is 219 yards to 100 grams. Broken down to yardage per gram (divide the number of yards by the number of grams; thankfully many yarns are measured at 100 grams and that’s easy division), we’re looking at (respectively) 22 yards to a gram; 18.6 yards to a gram, 27.2 yards to a gram, and 21.9 yards to a gram. Of those, I would be comfortable substituting Ella Rae Classic for Cascade 220, because their yardage per gram is closest. That means, before swatching, these yarns are likely to knit up at a very similar gauge and with a similar drape. They are both the same yarn content (though I will say that sometimes different breeds of wool can create variances after blocking, but usually they’re spot on).

Swatching

Yeah I know, no one likes swatching, swatches lie, blah blah. I don’t care. Swatch. When you have enough sweaters under your belt you can take crazy risks and fix things as you go, but for this first sweater, you need to swatch. You will get to the point that you can choose to skip it—I know now that if I use the same yarn that Amy Christoffers uses in her design, I can skip the swatching, but I’ve also knit at least five of her patterns. If I’m knitting something by a new-to-me designer, I always swatch. They may be a tighter knitter than you, or a looser knitter, and you need to know these things to determine the size you’re going to knit (see I told you these go together).

You want to swatch in the same manner that you’re going to be knitting—if you’re knitting a seamed pattern, you can knit a flat swatch, but if you’re knitting a sweater that’s worked in the round, you’re going to want to knit in the round. Many knitters suggest starting with a sleeve for your swatch, which works if your chosen pattern has sleeves. If it doesn’t, you can try Ysolda’s swatching in the round technique. I’ve had varied success getting an accurate read with that way of swatching, but it’s definitely good to try.

Work your swatch in the stated pattern—many times it’s stockinette stitch, but sometimes it’s in a chart or a colorwork pattern. Please do not only cast on the number of stitches listed in the gauge—that’s not how the finished gauge was measured in the pattern and that’s not going to give you the best sampling. I like to cast on 50 stitches for my swatches. Yes, 50 stitches for every single swatch. Unless that’s just ridiculous, like when I’m using a bulky weight yarn and the stated gauge is 10 stitches over 4″ or something like that. In those instances, go with at least two times the stated stitch gauge.

The most important thing is to measure your swatch before and after you wash it. You want to know how your yarn is going to grow after its bath. If I had done this step, I would have known that my Vivian sleeves were going to grow like crazy after they were washed. Write down your pre-block stitch and row counts, then check them again after the swatch is dry.

Choosing a Size

You want to swatch before you choose your size (which can be a catch-22 if you’re using a sleeve to swatch) because you may find that you’re knitting a different size than your measurements. I’m going to look at the Iðunn pattern from Knitty because I’ve knit it (even if I made it a pullover instead) and am familiar with the numbers.

The stated gauge for this pattern is 19 stitches and 26 rows to 4″. That’s 4.75 stitches to one inch, and 6.5 rows to one inch. If you’re knitting this sweater and that’s your gauge, choose the size that closely matches what you want—if you’re a 34″ bust and you want 2″ of ease, you’d pick the 36″ size. If, in your “what do I like to wear” assessment, you discovered you like looser sweaters, the 40″ might be the size for you.

But for the sake of argument, let’s say your gauge is 4 stitches to one inch, or 16 stitches to 4″. You’re knitting at a looser gauge than the sample knitter who knit the original pattern. It’s a complicated relationship—if you’re getting fewer stitches in your gauge, you’re knitting loosely and need to go down a size. If you’re getting more stitches, you’re knitting tightly and need to go up a size.

Another way to think about it is if your stitch gauge is lower than the stated gauge, you need a lower needle size; if your stitch gauge is higher than the stated gauge, you need a higher needle size.

You can swatch again on a different needle size to see if you can get the stated gauge. OR, if you’re not afraid of a little algebra (and it can be scary) and you really like the fabric you’re getting at your gauge, you can do some really simple math (I promise, it’s simple, and you can do it).

Looking at the Iðunn pattern again, the sweater says to cast on for 89 stitches for the smallest size. We’re going to take that number and divide it by the gauge. (I really wish they’d listed neck opening numbers on the schematic to double-check the work.)

89 stitches divided by 4.75 stitches per inch equals about 18.75 inches

But that’s not the gauge we’re getting.

89 stitches divided by 4 stitches per inch equals 22.25 inches

At our example gauge, the neck opening is going to end up almost 4″ wider.

Let’s do this again with the bust measurements. Well, for Iðunn, we’re going to use the numbers at the widest part, since there’s no easy way to see the stitches after the sleeves are separated—”After working all increases in the chart, you should have 260[276, 300, 308, 324, 356, 372] sts on your needles.”

Again going with the smallest numbers (and in a seamless sweater, this is counting the body and the sleeves, so don’t freak out thinking these are the bust numbers):

260 stitches divided by 4.75 stitches per inch equals 54.75 inches around.

But with the gauge we got:

260 stitches divided by 4 stitches per inch equals 65 inches around.

That’s a ten inch difference in circumference.

So you can use this really simple math check to determine which size you should knit, if you don’t want to swatch over and over again to get the exact stated gauge. And the truth is, there will be times that you can’t get the exact stated gauge—knitters are just different in that way. If you’re within a half a stitch over 4″, you’re probably safe to go ahead. Just compare your gauge to the stated gauge, double check some of the numbers against the schematic measurements, and then choose the size that most closely fits what you want from your sweater (generally your bust size plus however much ease you’re comfortable with).

But then (there’s always a but), you’re also going to want to check that your chosen sweater will fit your shoulders. I’d go on and on about it, but Amy Herzog already explained it better than I could and I can feel your eyes glazing over after nearly 2,000 words about yarn and swatching. So go get a cup of coffee or tea or whatever, take a break, read Amy’s post, and then sit down to swatch for your first sweater.

[…] a sweater is going to be worth it. I’ve got more in-depth thoughts on swatching in another blog post (that’s right, I’m going to save you the full talk this […]

[…] wrote about yarn substitution about six years ago, in this very long blog post. If you’ve been around knitting social media this weekend, you’ve probably seen some […]

[…] talked about how I knit a swatch before, and probably will again. Today I’m focusing on how I knit swatches that are more […]